Why Investigate Relational Art in the Context of a Pandemic?

To direct one’s research focus towards relational practice in the midst of a pandemic crisis seems paradoxical at first: how can relational art, “which takes being-together as central theme,”1 continue to exist if social-distancing is the new behavioral norm? In a world with increasing limitations on physical connection, art explores alternative domains. Digital platforms, social media and other forms of virtual hubs have mushroomed as physical art spaces went into lockdown. But what does that mean for an art practice that cannot be summoned into digital imagery? Can a physical experience really sustain its impact through the interface of the screen? Or can physical involvement be replaced with other imaginative methods? Can one mediate spontaneity into the virtual? And is it possible to engage the same intellectual and emotional involvement in a digital dialogue-setting as if it were face-to-face? In essence, we must question whether relational art can continue in its previous form throughout the pandemic’s restrictions, or if it will ultimately undergo a rebirth into a more hybrid form, reflecting the now heightened condition of living between multiple realms.

To question the doom of relational art means to first understand its constituent parameters, which is not an easy undertaking. There are many synonymously used terms for relational art, depending on the angle from where it is looked at. The wide spectrum of definitions encompassing the field has to do with the many critical voices that played into establishing and de-constructing this practice.

Drawing from a few prominent arguments from the past discourse helps us understand the critical stance on relational art before the pandemic. From that point, I investigate three examples of relation-based practices that have occurred over the past weeks as the pandemic began unfolding. The goal is not to categorize these current relational practices with regard to their precedents. In contrast, I intend to first demonstrate how relational practices until now have been discussed in a canonist perspective. By using the three examples, I challenge old narratives of relational art and explore how each exemplary case fits into contemporary conditions.

Definitional Dilemma around Relational Art

In the 1990s the French curator and art theorist Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term relational aesthetics, which refers to a vast set of emerging artistic practices that focus on “inter-human relations” rather than visual experience.2 He pushed for a general recognition of art that no longer represented but constituted “ways of living and models of action.” Bourriaud argued for “artwork as social interstice”, specifying this abstract term with a long list: “meetings, encounters, events, various types of collaboration between people, games, festivals, and places of conviviality, in a word all manner of encounter and relational invention.”3 Bourriaud built his argument on the grounds of sociological observations. For example, he observed that the share of interactivity increased due to the rise of new communication tools and individual mobility. According to him, these urbanization phenomena produced an increase of open-mindedness and “a collective desire to create new areas of conviviality”.4

But Bourriaud’s attempt to subsume all relational activities under an umbrella of solely positive bonding experiences was met with high criticism by a range of scholars, writers and curatorial practitioners. With the onset of Claire Bishop’s article Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics, Bourriaud’s theory of relational aesthetics started to be challenged for its shortcomings: “The relations set up by relational aesthetics are not intrinsically democratic, as Bourriaud suggests, since they rest too comfortably within an ideal of subjectivity as whole and of community as immanent togetherness.”5 Bishop redirects the focus towards the existence and validity of art that exposes dysfunctional relationships, which are just as equally inscribed into our social lives. To acknowledge such practices, ethical criteria cannot be the primary grounds upon which contemporary artistic practice is judged.6 Because antagonist art, as Bishop coined it, serves an important purpose: it refrains from enforcing utopian enclaves, so called “microtopias”, and instead directs public attention towards relations that manifest in abusive realities: “relational antagonism [is] predicated not on social harmony, but on exposing that which is repressed in sustaining the semblance of this harmony [and] thereby provide a more concrete and polemical grounds for rethinking our relationship to the world and to one other.”7 Bishop developed her argument with close attention to political science, particularly the politics of antagonism and agonism.8 She believes that artists who reproduce conflict and friction as a form of art point towards systemic injustices. And only if art awakens consciousness about these prevailing injustices, is change possible.

The argumentation so far mirrors two opposing categories: relational conviviality versus relations of dissent. In reality, these relations are of conflicting nature. They can contain constructive components and be destructive in other areas at the same time. In this regard, neither the works celebrated in Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics nor the antagonist practices propelled by Bishop provide insight into the richness of relational complexities. And perhaps at the root of this is that, in both cases, relations are “modelled” in an aesthetic context.

This is where socially engaged art takes a different approach. Instead of staging scenarios for art publics, socially engaged art takes place ‘outside the art system’. In fact, practitioners of socially engaged art are highly skeptical of relational aesthetics, as the following quote by artist and activist Josh MacPhee demonstrates: “I am tired of [relational] artists fetishizing activist culture and showing it to the world as if it were their invention.”9 Socially engaged art is often seen as fieldwork. Diving into a community, embracing a locality and offering a contribution are characteristics of this practice.10 Often there is a focus on social work and community-building with a creative dimension. In these practices, questions concerning authorship and formal aesthetics are of secondary order: “Defying discursive boundaries, socially engaged art’s very flexible nature reflects an interest in producing effects and affects in the world rather than focusing on the form itself.”11

Socially engaged art welcomes diverse approaches. However, such openness brings about an often-indiscernible entanglement between artistic and social work. Consequently, it is not always possible to exactly understand where the ‘art’ lies, nor is socially engaged art necessarily exhibit-able. This is precisely the point: to defy the representational by equating art with action. But there’s an important point of critique in regard to combining social engagement with artistic agency. Architect and researcher Sandi Hilal points out that artists practicing socially engaged art with the intention to “give voice” to a community, should carefully reflect on what grounds they are entitled to do so: “It’s crucial [that socially engaged art is] not for others, it’s not about others, it’s not to enable anyone.”12 What Sandi Hilal is aiming at, is that socially engaged art should not produce a dichotomy of “me vs. they”, because then the art reinforces supremacist patterns of authorization, which is counterproductive and offensive. Instead, if the artists become part of the community they are working with, the collaboration occurs at eye-level.

Relational art, relational antagonism and socially engaged art are only three key terms in the definitional debate around interactivity in the arts since the 1990s. In the past three decades, many more hybrid forms of relation-driven art have emerged. Among these are, for instance, archival practices as theorized by Hal Foster,13 or new forms of experimentation between art and sociology, such as Irit Rogoff’s interdisciplinary approaches known as “advanced practices”.14

The question is: What comes out of this terminological overflow and the many nuanced approaches to relations in the arts? Firstly, referring to an art practice today as ‘relational’ is problematic, considering how strongly this term is associated with Bourriaud and the league of artists he has been working with. In other words, the term ‘relational’ in the context of contemporary art has in and of itself become “art-historized”. It is worth noting, that in the 1990s many of these works were conceived in order to rethink the museum and gallery space into a more flexible, spontaneous zone. Hence, relational art back then contributed to institutional critique. As valid as the efforts and achievements from that period were, artists working in ways that investigate relations today do not necessarily stand in direct genealogy to relational aesthetics from the 1990s. This assumption would propose a linear perspective on artistic cohesion, which does not do justice to the many influences behind each individual practice.

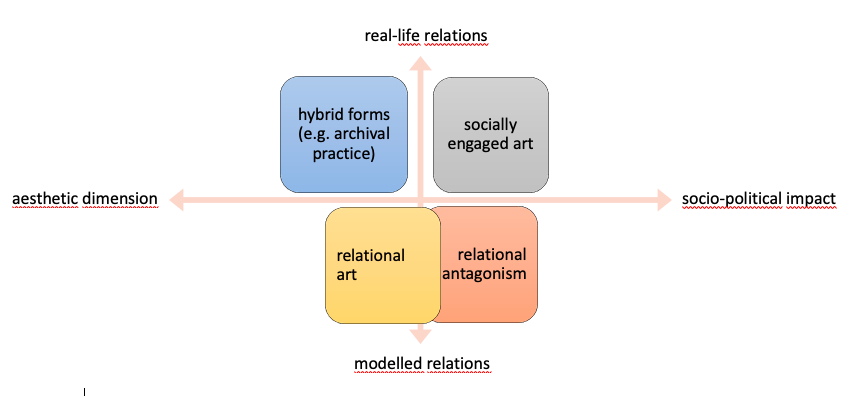

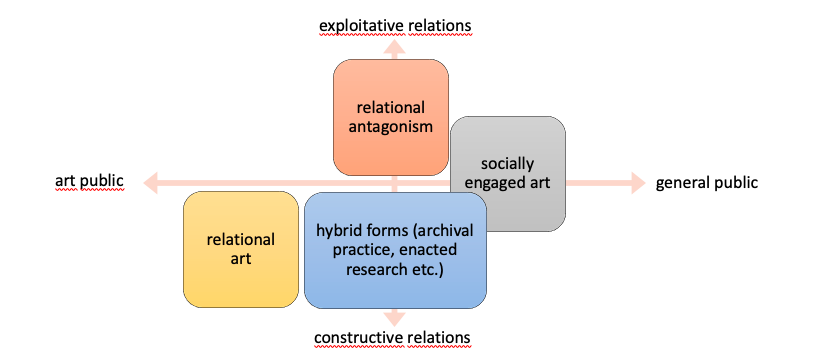

Moreover, clustering relational art in a matrix according to criteria that is used in the theoretical discourse only reveals that some of the practices classified as opposing each other, actually have criteria in common:

The matrix-perspective shows that relation-driven art can be of ambiguous nature. For instance, as socially engaged art is concerned with constructing relations within a community, it often does so by addressing relational deficiencies. Another example: antagonist art explores conflictual relations present in the real world but caters the outcome to an art public. These ambiguities are in the center of my further analysis. Instead of reproducing an ‘either/or’ perspective from the old discourse, I focus on where ambivalent forces emerge and what that tells us, not just about the state of the art, but also about the state of society.

Art and Relations Amidst the Pandemic. A Case Study Approach

In the following, I introduce three case studies of relational artistic practices that have intersected with the pandemic context. Again, it is important to remember that ‘relational’ in the context of the further analysis means neither relational in Bourriaud’s (constructive) sense, nor in Bishop’s (antagonist) sense, nor is it socially engaged art or any other classification. Here, the relational is subject to negotiation. This means that with each case study it is questioned what type of relations emerge and how they are in interplay with the pandemic.

Felix Gonzales-Torres, Untitled (Fortune Cookie Corner), 1990 / 2020

A few weeks into the pandemic and first global lockdown, New York based art dealers Andrea Rosen and David Zwirner, who co-represent Felix Gonzales-Torres' estate, staged a global showing of the late artist’s work Untitled (Fortune Cookie Corner) from 1990.15 In the context of the artist’s oeuvre, this particular work marked the beginning of his signature-style Candy Works. Untitled (Fortune Cookie Corner) is made up of a stack of fortune cookies offered to be taken away for free and eaten. This new series of works biographically coincided with the passing away of his life partner, Roni Horn.16 Hence, the personal experience of loss and transformation becomes manifest in the relational dimension of the art as the pile of candies is gradually carried off. The installment of the work follows a set of instructions, which underpin further aesthetic, metaphorical and poetic dimensions of the work.

In May 2020, Rosen and Zwirner announced a restaging of Untitled (Fortune Cookie Corner) in various international locations. The artist’s instructions allowed the work to be executed in multiple places at the same time. Likewise, the pile of cookies could be placed anywhere the executing parties chose: indoors or outdoors, in the private or public sphere. The estate-managers marketed their initiative as a global invitation to participate in the experience of loss, grief and transformation.17 But that aspiration, to reach out to a global public, clashed with the fact that they leant the work and its instructions to only one thousand selected participants.

Here, the problem of exclusiveness arises. Andrea Rosen and David Zwirner, house-hold names in the high-end art market, carefully picked out a circle of people. A spokeswoman of David Zwirner openly admitted: “the invited participants are a diverse but specific international group that includes writers, curators, artists, colleagues, friends of people involved in the projects and friends of Felix’s, people who have posted Felix’s work on Instagram.”18 This quote exemplifies an attempt to democratize and justify the choice, but the selection still remains solely amongst an art-related public, whether they are collectors or art influencers on social media. Now why does this matter in the context of the artwork and its global staging amidst the pandemic? By authorizing only a selected crowd to execute the piece, ‘art mictrotopias’ were re-erected. Even if they spanned across the globe, the work circulated among insiders. Restaging the fortune cookie corners in this way falls short of acknowledging the pandemic’s impact on the entirety of humanity. Though it appears as if there were a full negligence of that exclusiveness on the initiator’s side: “everyone has the opportunity to experience both the potential loss within the piece, and also the notions of rebuilding and regeneration that is a very important part of the work” said Rosen.19 The rebuilding and regeneration that Rosen mentions here, refer to the fact that each executor of the work was instructed to refill the pile halfway through the exhibition’s duration. Though by saying ‘everyone’, Andrea Rosen really means ‘every designated one’. The way this project was staged with a pre-selected range of participants lays bare how the art public perpetuates a self-isolating spirit. In the context of the pandemic, this comes as a missed chance to break away from old patterns and really constitute a worldwide inclusive outreach.

For instance, if the resurrection of relational works such as Untitled (Fortune Cookie Corner) was announced in an open-call through international, non-art-specific media, it could have motivated the participation of people unaffiliated with the arts. This could have manifested in fortune cookie corners going viral, appearing in most unexpected places. Of course, this would require the initiators to comply with losing control over the artwork’s authorship, which could have negatively influenced market value of the artist, hence, causing a clash of interest.20 Nevertheless, a truly comprehensive staging of the work could have sparked engagement among communities that lack cultural infrastructure. Had Rosen and Zwirner included the broader public, they would have paid tribute to Gonzales-Torres’ relational approach: one that aesthetically and conceptually urges the public to collectively cope with existential fears.

Simona Andrioletti and Riccardo Rudi, Chinese Whispers, ongoing since 2018

While the restaging of Felix Gonzales-Torres’ Fortune Cookie Corner fell short of spreading a unifying sentiment beyond the art system, Chinese Whispers by Simona Andrioletti and Riccardo Rudi succeeds in creating just that: a diversified community. The two artists began collaborating on this project in 2018 and continue until today. Chinese Whispers21 takes inspiration from Giuseppe Ungaretti’s poem Girovago (The Wanderer) from 1918.22 It tells the story of a restless traveler in search of an innocent land. The two artists ask to record expats in different locales as they recite the poem in their respective mother tongues. These recordings function as archives and transmitters of the participants’ deeply personal, yet collectively shared longings. The recordings are then emitted through loudspeakers into the surroundings, both indoors and outdoors: “Chance plays an important role in the way Chinese Whispers reaches out. We have seen people who only accidentally overheard the poem being recited in their native language respond to it in emotional ways.”23

As Simona Andrioletti points out, the way Chinese Whispers is transmitted welcomes the interference of passersby. In fact, the work further undermines the concept of an art community with a second element: The artists produce scarves that adapt the aesthetics of soccer fan gear. They are then sold at typical fan gear price both online and on-site where Chinese Whispers is presented. Each scarf contains the last line from Ungaretti’s poem in two different languages, stating ‘I seek an innocent land’. The languages differ with each new edition of the scarves.24

Mimicking fan gear, the Chinese Whispers scarves claim the status of a pop cultural symbol. Those acquiring and wearing the scarf identify with the message. Hence, they become innocent land seekers of their own. The relational dimension of this work expands beyond the particular experience of being a geographical foreigner. On a meta-level, the work is about continuously searching for one’s identity. An emotion which is individually experienced but shared with others, which produces togetherness in a constant flux: not one collective identity but ever-changing collectives between stages of belonging and stages of moving on. Chinese Whispers addresses the human quality of yearning to belong somewhere even against the odds of ever finding that place.

This relational component became even more evident in the course of the pandemic, as Simona Andrioletti describes: “People have started reposting the scarves more and personally reaching out to us, saying the pandemic has enforced their feeling of seeking an innocent place.”25 Furthermore, she elaborates, that through the current crisis-lens, people see yet another layer: “Chinese Whispers is now about feeling distanced to what used to be familiar.”26 The quote brings two important aspects to the fore: First, the relational dimension is no longer focused on the interpersonal. It has now shifted to include the ways we relate to conditions of the past and the present. Secondly, this new relational prospect does not model or spur connectivity but rather points to the lack of it.

During the pandemic, Chinese Whispers was staged at Wörthsee in Bavaria on 2nd October 2020. In this latest rendition, actor Herbert Volz recited the poem through a megaphone as he was standing on board of a Venetian gondola crossing the lake. Here, the artists are referencing Werner Herzog’s iconic movie Fitzcarraldo (1982), where the protagonist aspires to build an opera house in the depths of the Peruvian rainforest. In the movie, when the original mission fails, Fitzcarraldo turns his boat’s deck into a stage for a one-time-only opera performance. When Chinese Whispers is staged on a gondola amidst the pandemic, purposefully evoking parallels to the storyline of Fitzcarraldo, the work sets an example for the continuation of art despite all hurdles of the current crisis.27 One can question the absence of the public, though the very point in Fitzcarraldo’s epic performance is the personal satisfaction he draws from it. Quite similarly, the staging of Chinese Whispers in the remote location of Wörthsee did not target a crowd of intentional listeners. The recital primarily affected the crew of actors, artists, videographers and the gondoliere. At the same time, the megaphone carried the poem across the lake and into the natural landscape. As the words echoed back, the experience evoked the very primal relational dimension between men and nature. Consequently, in this particular setting, Chinese Whispers also re-opened the dialogue between seekers of innocent land and their immediate environmental surroundings.

Abir Kobeissi, Kauf mir einen Aufenthaltstitel (Buy Me A Residence Permit), 2020

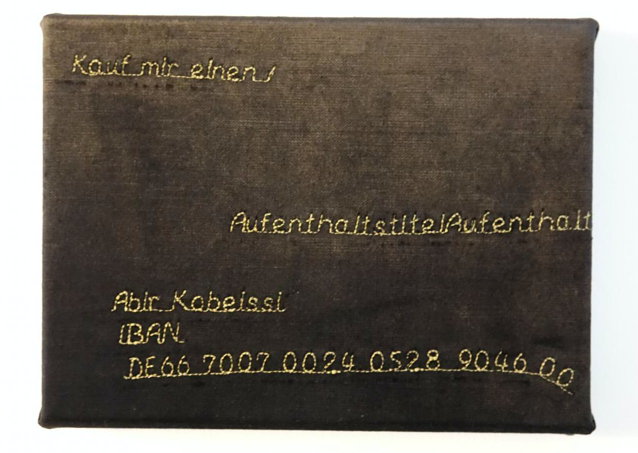

Buy Me A Residence Permit28 was born out of a bureaucracy-related vulnerability Lebanese artist Abir Kobeissi came to personally face over the course of 2020. An international student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, Abir Kobeissi is required by state law to maintain a statutory amount of ten thousand euros on her bank account. As the pandemic broke out and the artist lost her student job, she could no longer secure the non-disposable capital. Kobeissi then turned her personal state of emergency into a relational approach in the form of a direct appeal: Buy Me A Residence Permit became a relation-driven artwork consisting of a verbal request disseminated through local press and its answer in the form of a money transfer.29

The original title in German Kauf mir einen Aufenthaltstitel is also the name of another artwork by Kobeissi where she stitched the appeal next to her bank information on framed velvet. In this piece, relational dimensions overlap with aesthetic and iconological qualities, such as the connotation of velvet in an art-historical perspective, which stands for luxury and political power. Also, the stitching is a cultural reference towards textile art which, despite feminism’s progress, continues to be closely associated with the feminine. Parodying the neat and small format of historical domestic stitching, Kobeissi subverts the notion of shelter and safety, making her existential endangerment the subject matter. Despite her being enrolled as student in an educational institution, her existence as an artist is endangered by administrative barriers. These, her case demonstrates, can apparently only be overcome by individual action of patronage, which then consolidate unjust conditions, that mark societies of affluence.

Yet, the artist separates the embroidery from her call-up in the press. If anything, the verbal appeal is an extension of what she has been doing in her visual, object-based art into another media. In a personal interview, she comments on why she felt an urgency to use language and the commanding tone: “Words are direct. They demand an action way more explicitly than visual vocabulary.”30 Concert promoter Scumeck Sabottka, who donated the amount needed, admired the artist’s straightforwardness.31

But there is more to Kobeissi’s choice of tone than directness. She was disappointed with the German bureaucratic system for not easing their pressure on her, in spite of the pandemic and the financial crisis in Lebanon, where Kobeissi is originally from. In her appeal, she tried to convey the uncompromising attitude that she encountered in German bureaucracy. That’s why Kauf mir einen Aufenthaltstitel addresses someone in German.

The antagonist sentiment that radiates from Buy Me a Residence Permit is a crucial component of the work’s effectiveness. Abir Kobeissi exemplified her own case, in order to draw attention to an infrastructural gap in the support of international students. Moreover, the way her personal situation could be remedied with just one bank transfer, speaks of the systemic social divides resulting from unequal wealth distribution in capitalism.

The Way We Relate Now – Relational Art Practices During the Pandemic

The three art practices discussed here show how the crisis heightens our awareness of relations beyond simplified, one-sided versions. To answer the lead question, if relational art can reconstitute a sense of connectivity in the age of social distancing, has meant to recognize what connectivity means these days: To whom and to what do we now relate and how? Each case study provided a more complex perspective on this:

The 2020 rendition of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (Fortune Cookie Corner) exemplified that while the artwork’s instructions support the idea of connecting geographically disparate locales, the way it was spread within an art public by the dealers Zwirner / Rosen purposefully reduced the initiative’s impact to a selected crowd. This gave evidence for a persisting desire within certain parts of the art system to strengthen bonds with one another rather than opening up to unexplored terrains. With regard to the conceptual core of Gonzales-Torres approach; the ‘art’ of withdrawing and eating as a way of partaking in and transforming grief, lends itself well to reflect the pandemic experience. This means that a restaging per se can be a valuable contribution if it were open access. This way, the important component of refilling the stack half-way through the exhibition should be accessible to every participant equally. The relational dimension in this act of refilling is concerned with care, an ‘essential service’ which in the context of the current health crisis finally gains indisputable relevance.

With its multiple components of poetry and symbolic gear, Chinese Whispers continuously grows as a physically scattered, but emotionally connected community of the likeminded. Reflecting on the search for identity in a crisis not only revives questions of belonging, but also produces the notion of yearning for ‘normality to return’. Our relation to time, whether nostalgia towards the past or hope towards a future, is a central theme emerging from Chinese Whispers seen in the context of the pandemic.

Finally, Abir Kobeissi’s subversion of bureaucratic mechanisms in Buy Me a Residence Permit fostered a one-on-one connection between artist and donor, while it counteracted the system of social injustice. Herein, she exposed relational insufficiencies and dysfunctionalities in the supposedly reliable safety net of education. With her verbal appeal through local and national press, Kobeissi succeeded to catch public attention to her personal matter, which exemplifies these broader issues. Now the question is whether her appeal radiates beyond situational urgency and if her story can be the spark for changing deficiencies in the bureaucratic system.

In the end, one of the strongest insights emerging from the practices presented here, is their scrutiny towards the many facets, ambiguous and hybrid nature of connectivity in the new realities we inhabit. Connectivity is no longer seen as a static construct, but revealed as a form of action, as a mental state of mind. Connectivity can be porous or of continuous nature. It can manifest itself in the carrying of symbols, or it can be a once-only money transaction. This hybridity concerns the entire field of relational art practice now. The clear-cut division pursued in art theory no longer applies to a diversified, versatile, and trans-disciplinary condition of artmaking. Now the relational dimension is not a signature style, but an always resonating component within art practices occurring between the physical and digital realm, between action and representation. The pandemic only highlights this development, as it brings attention to overseen relational dimensions in contemporary society. Here, lies the potential for artistic practice involving the relational – to unveil ambiguities of the present.

-

Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les Presse Du Reel, [1998] 2002, p. 15. ↩︎

-

Ibid., pp. 13-14. ↩︎

-

Ibid., p. 28. ↩︎

-

Ibid., p. 26. ↩︎

-

Bishop, Claire. Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics. October 110, Fall 2004, pp. 51-79. ↩︎

-

Bishop, Claire. The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents. Artforum, Feb 2006, pp. 178-183. ↩︎

-

Bishop 2004, p. 79. ↩︎

-

Mouffe, Chantal. On the Political. Thinking in Action. Abingdon: Routledge, 2005. ↩︎

-

Josh MacPhee qtd. in Thompson, Nato. Living as Form. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2012, p. 31. ↩︎

-

Kester, Grant. Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art. Cambridge, MA: University Press Group Ltd., 2004. ↩︎

-

Thompson 2012, p. 32. ↩︎

-

Sandi Hilal qtd. from a lecture she held in the framework of Unidee Residency Program Embedded Arts Practice in a Post-pandemic Future, 17 October 2020. ↩︎

-

Foster, Hal. (Dis)engaged Art. in: Right About Now: Art and Theory Since the 1990s, eds. M. Schavemaker and M. Rakier. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2008, p. 73-85. ↩︎

-

Rogoff, Irit: Becoming Research: The Way We Work Now. Lecture at the MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology, 9 April 2018, uploaded on Vimeo, https://vimeo.com/271887079, (accessed 4 September 2020). ↩︎

-

Durón, Maximilíano. Thousands of Fortune Cookies to Be Offered as Art in Largest-Ever Showing of Felix Gonzalez-Torres Work. ARTnews. 5 May 2020. ↩︎

-

Felix Gonzales-Torres. Guggenheim Collection Online. https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/felix-gonzalez-torres (accessed 15 August 2020). ↩︎

-

Cascone, Sarah. Want a Gigantic Pile of Cookies in Your Home? 1,000 People Are Being Asked to Hoard Fortune Cookies as Part of an Ambitious Global Art Show. Artnet News. 7 May 2020. ↩︎

-

Harris, Gareth. Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s fortune cookie piece to pop up in 1,000 locations worldwide. The Art Newspaper. 7 May 2020. ↩︎

-

Andrea Rosen qtd. in Cascone, Artnet News, 2020. ↩︎

-

It is worth noting that the restaging of this work coincided with the re-launch of the artist’s estate website, revealing further image marketing intentions. ↩︎

-

The project title Chinese Whispers is based on the eponymous internationally popular children’s game where a whisper is spread from one ear to another until finally the message is revealed. ↩︎

-

See https://simonaandrioletti.com/chinese-whispers-2018 (accessed 30 October 2020). ↩︎

-

Simona Andrioletti qtd. from a personal interview I conducted with the artist on 24 October 2020. ↩︎

-

More information about the editions can be found online: https://chinesewhispers.club/scarves (accessed 30 October 2020). ↩︎

-

Simona Andrioletti qtd. from a personal interview I conducted with the artist on 24 October 2020. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Originally, the gondola was supposed to cross the Nymphenburger Channel in central Munich, addressing passersby around the channel. The Cultural Department of Munich had already approved of the project and its location, but the Bavarian Palace Administration overturned the endeavor last minute. ↩︎

-

The original title of the work is in German: Kauf mir einen Aufenthaltstitel. ↩︎

-

Abir Kobeissi contacted Süddeutsche Zeitung and was then interviewed by the journalist Ornella Consenza. Monopol art magazine then published a review of the appeal and the donation it resulted in on 30 June 2020. https://www.monopol-magazin.de/abir-kobeissi-kauf-mir-einen-aufenthaltstitel (accessed 30 October 2020). ↩︎

-

Abir Kobeissi qtd. from a personal interview I conducted with the artist on 16 September 2020. ↩︎

-

Consenza, Ornella. Angst vor der Heimkehr. Süddeutsche Zeitung. 03 May 2020. ↩︎